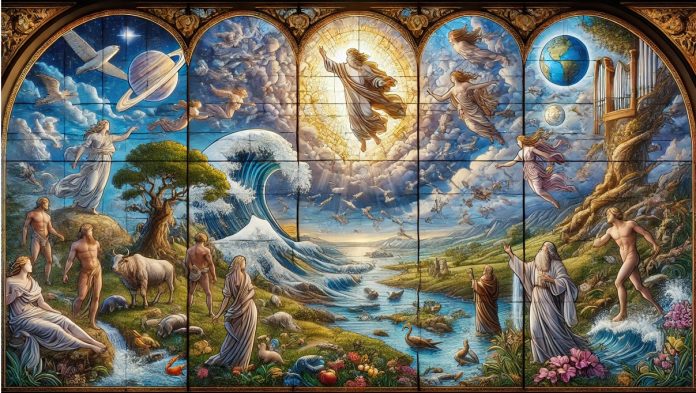

In the beginning God created heaven and earth.

When you think heaven, you probably think stars and shit. But no, those were created on the fourth day.

We’re still on day one here.

Meanwhile, the earth was really dark, and God was blowing his Godly wind all over the water. It was chaos, all that wind. Total chaos.

And then God said, “let there be light”, and there was light. But not from the sun, that’s still happening on day four, as you might recall.

God liked where this was going and decided to separate the light and the dark. Until then they had been mixed.

And God called the light “morning” and the darkness “evening”, which is why in parts of Sweden they have one morning and one evening per year.

And thus concluded the first day.

Day two. God focused on firming up the firmament. He placed it between the upper waters and the lower waters, and so it was.

At this point you might be asking yourself what firmament is. Who knows. It sounds like one of those things your contractor tells you he was working on when you ask him for a progress report. Basically, he spent an entire day doing fuckall, as far as can we can observably tell. Slacking off on the second day of the job.

Day three, water works. God gathered all the waters into one place, so that the earth was exposed. His words, not mine. And then he gave things names like “land” and “sea”, but in Hebrew. Accept no substitute for the original Hebrew word.

Now that there was land, God created grass and fruit trees. As a reminder, there was still no sun for photosynthesis and no creatures for pollination, but whatever.

On the fourth day, God finally attended to the celestial bodies. After focusing mostly on blades of grass the day before, he then went on to create the entire solar system. He made the sun. He made the moon. And oh, yeah Ii almost forgot, he also made billions of stars. And these celestial bodies are there to tell the difference between day and night, not to be confused with “morning” and “evening” from day one. It’s a subtle but important difference.

On the fifth day, God moved on to living creatures, water insects, birds, really big serpents. That was all for the day, but he made a shitton of them, and he instructed them to multiply further. Fruitfully.

We’re almost done here. On the sixth day God created the animals and the land insects. Oh, and also man. And conveniently, he created man and woman in his own image and told him to rule all the other animals. And he also told them specifically to eat plants and fruits and be vegetarian. And he told all the animals, even the carnivores, to be vegetarian as well.

And God thought that it had been a really good day. His words again, not mine.

* Record scratch. *

Man: “Let me tell you how I got here.”

Commence chapter 2, which inserts an entirely different story more in the style of Rudyard Kipling.

***

This is the story of the heaven and earth on the day that God created them.

There were no plants yet, because God had net yet invented rain nor man to water the ground. Then God invented vapor and watered the earth.

Then God created man, out of dirt, and puffed life into him.

Then god planted a garden in the front part of Eden, where real estate values were the highest, and put man there.

Then he planted all the good looking and delicious trees.

And then God put man in the Garden of Eden, again. (Supposedly he’d wandered off, like a badly programmed NPC)

And then God said, “it’s not good for man to be alone, I shall make him an assistant”.

So god created, again from dirt, all the animals and all the birds. and he brought them to man to name. And whatever man named them, such as “yellow breasted tit” and “blue-footed booby“, it stuck.

And yet, despite naming all the animals, he could not find himself an assistant.

So God put man to sleep, removed his rib, crafted it into a woman, and gave it to man.

Man said, “finally! I like that this is my own rib and flesh we’re talking about here. I shall call her ‘woman’, because it has the word ‘man’ in it and it comes from me“.

And that’s why men leave their mommy and daddy and cling to their wives as one flesh.

Oh, and by the way, they were both naked but not embarrassed. (which probably helps with the clinging as one flesh part)

That’s pretty much it. An unprecedented glimpse into the origins of time that were previously shrouded in mystery but are now clearly elucidated with two contradictory narratives.

A few more clarifications that unfold in later chapters and explain things as they are today:

Snakes used to have feet, like lizards, until God removed them. This is probably why they still have pelvic spurs. The bible is spot on, as usual. It’s also why human don’t like snakes. presumably beforehand they were deeply lovable creatures.

Woman gets cursed with “much sadness and pregnancy” and to give birth “sadly”. If that’s not enough, she is doomed to “yearning after men while being ruled by them”. Sad trombone.

Man, meanwhile is punished for listening to his wife and the land is cursed because of him – he must toil to create bread which he will then “eat sadly”. Also, he’ll die eventually, which apparently wasn’t gonna happen until then.

That’s pretty much it. Let’s wrap up any final details with a rapid montage.

Man realizes what it means to be naked and invents clothing made of fig leaves. God improves on the design by using animal hides. He might still be angry, but he’s not a dick.

Yaval invents shepherding.

Yuval invents musical instruments.

Tuval-Cain, with his fancy hyphenated first name, invented both copper and iron working, despite these occurring 1600 years apart.

Un-hyphenated Cain invents murder and sarcasm.

God invents rainbows 1,000 years later.

Man initially lives for hundreds of years, which then peters off into a measly dozens of decades before culminating in the pathetic 70-80 year lifespan we know of today.

Probably due to lifestyle changes.